Published: February 2, 2018

Angola’s new president is promising economic reforms to shore up the stricken economy, as the country prepares a US$2bn eurobond issue.

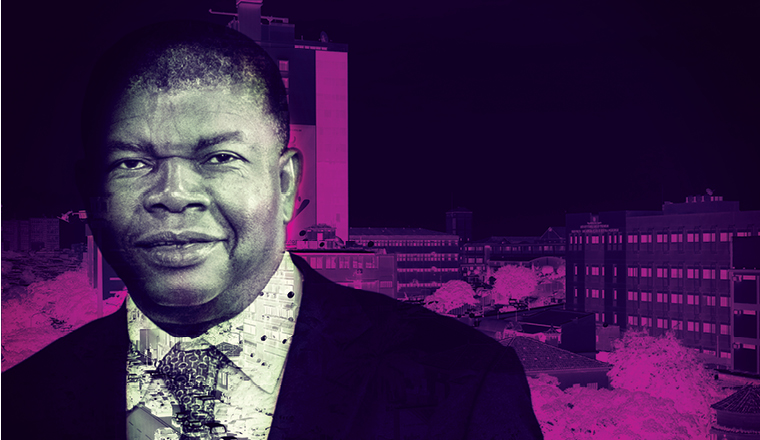

The inauguration of a new president is something that only a minority of Angola’s overwhelmingly young population had ever seen, until this September, when Jõao Lourenço took office. His predecessor, José Eduardo dos Santos, ruled Angola for close to four decades, overseeing the country through a long civil war, an economic recovery and, latterly, an oil price crash that pushed it back into recession.

For a brief period before the financial crisis, Angola was on the rise. One of the fastest-growing economies in the world, its oil reserves gave it sudden and enormous wealth, which it spent at home and abroad with considerable largesse. Then, slumping hydrocarbon prices turned it into a case study of how quickly boom can turn to bust in a commodity-based economy. Its new president faces an uphill struggle to reform and diversify away from oil, and is turning to international financial institutions and capital markets to do so.

“The downside risks to the Angolan economy remain the same as some years ago,” says Tiago Dionisio, assistant director at financial services boutique Eaglestone. “Angola remains very dependent on oil and so a drop in oil prices will have a negative impact on the local economy. Angola’s main trading partners include China, India and some Euro area countries. A slowdown in these countries will also hurt Angola’s growth prospects.”{mprestriction ids=“*”}

Angola is the second-largest exporter of oil in Sub-Saharan Africa, and its economic turnaround after its civil war ended in 2002 was almost entirely driven by surging exports. At its peak, the oil industry made up 40% of the country’s GDP and more than 90% of its export revenues. Some of that money was reinvested into public spending on services and infrastructure. GDP growth peaked in 2007 at 22.6%, and remained in double digits from 2004 to 2008.

Chinese money, which began flooding into Sub-Saharan Africa in earnest in the early 21st Century, was particularly attracted to Angola. China needed to meet its growing energy demands, and its approach of bartering infrastructure in exchange for commodities was a good fit for Angola, whose infrastructure had been badly damaged during the civil war and never repaired. The government in Luanda began to push for a greater role in the wider conversation about African economic development, using its growing sovereign reserves as leverage.

By the time the 2009 financial crisis hit, the wheels were starting to come off, however. Growth slumped. The 2014 collapse in the oil price, from over US$110 per barrel to below US$50, took the bottom out of a falling market and Angola tipped into recession in 2016, with the economy contracting by 0.7%.

Without the backing of the hydrocarbon industry, the pressure on Angola’s currency rose dramatically. The kwanza has lost around 40% of its value since 2014, at least at its official rates.

The black market rate is far higher, however, at one point hitting 600 per US dollar, against the official rate of 168. Today it has slipped back to around 350 to the dollar on the black market.

Inflation soared to 41% in 2016. It has since fallen, but it is still high, at nearly 30%. Angola is heavily dependent on imports, from staples to construction equipment, and the collapse of the currency has had a severe impact on the prices of basic goods.

Angola has piled on debt to plug the gaps in its budget. The country launched its highly-anticipated debut eurobond in 2015, raising US$1.5bn in a 10-year bond at a yield of 9.5%. The country also turned to Beijing for financing. The terms, and even the counterparties, of those transactions are opaque, and estimates range as to the value of Chinese lending, which could be as high as US$25bn.

Undisclosed debt is a warning sign for bond investors in Sub-Saharan Africa, where some had their fingers burned when Mozambique admitted in 2016 that it had US$1bn in previously undeclared loans, causing the International Monetary Fund to suspend its support. Mozambique ultimately defaulted on its eurobonds in 2017.

Angola is not Mozambique, but there are already worries about the sustainability of its debt load. In August, Standard and Poors downgraded Angola’s sovereign credit rating from B to B-. Moody’s followed suit in October, adjusting its rating from B1 to B2 with a stable outlook.

Both rating agencies cited rising debt service costs, exacerbated by the kwanza’s loss in value, a shortage of foreign currency liquidity and a weakened banking sector.

“Fiscal strength has materially decreased with indebtedness nearly doubling in the past four years, while liquidity risk remains elevated due to significant gross borrowing requirements. The debt-to-GDP ratio remains vulnerable to further currency devaluation and potential crystallisation of contingent liabilities from the public sector,” Moody’s said.

Angola’s finance ministry said in August that it plans to issue another US$2bn worth of eurobonds to lengthen the maturity of its existing debt profile and to create a benchmark for other local issuers. The timing of the bond issue has not been announced, nor have any banks or advisors been confirmed. Goldman Sachs and JP Morgan advised the Angolan government ahead of its 2015 bond issue. Deutsche Bank, Goldman Sachs and the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China International worked on marketing the bond in the US and Europe.

“The country seems capable of servicing its international debt obligations within the current context, but there are substantial downside risks,” says Jean-Philippe Pourcelot, Angola economist at FocusEconomics. “A decline in oil prices could dent oil earnings and fiscal revenues as a result. A possible devaluation of the kwanza would make foreign currency-denominated debt more expensive and make it more difficult for the country to pay its international debt obligations.”

The credit rating downgrades are also likely to push up the cost of borrowing, he adds.

There are other challenges. The banking sector has taken a pounding. The system’s capital adequacy ratio slid to under 19% in 2016, and non-performing loan ratios were up to 15.25%, as slowing growth and remaining exposure to the oil and gas sector hit corporates’ ability to service their debt.

In October, Lourenço appointed a new central bank governor, José Massano, who previously held the role between 2010 and 2015. Shortly before Massano’s appointment, the central bank announced an agreement with the International Monetary Fund, which will provide technical assistance on banking supervision and on anti-money laundering, in order to bolster the credibility of the domestic financial sector, and to improve Angola’s standing with international financial institutions.

Angola’s relationship with the Bretton Woods institutions could be significant. In 2009, at the height of the financial crisis, the Fund approved a US$1.4bn loan package. The World Bank subsequently agreed a US$650mn, facility in June 2015. The following April, with conditions in the Angolan economy still weak, the IMF offered Angola a US$1.5bn, three-year facility, which was characteristically contingent on wide-ranging economic reforms.

The talks ended in July, with Angola saying that it no longer wished to proceed. Then-finance minister Armando Manuel was subsequently fired and replaced by Archer Mangueira, previously head of the capital markets authority. Local press linked Manuel’s dismissal with the breakdown in talks.

Mangueira, who has retained his job under President Lourenço, has said that he intends to resume talks with the IMF, which is due to make another assessment visit of the Angolan economy. In its last assessment, released in December 2016, the Fund said that Angola needed to reduce its fiscal deficit and improve its non-oil fiscal balance by mobilising more non-oil taxes, reducing spending and increasing public investment. It also called for a move to “a flexible but managed exchange rate regime”, and for the government to announce a timetable for the removal of its exchange controls.

IMF backing has helped other countries in the region to shore up their finances and raise money on the international markets.

“I think the resumption of IMF support to Angola would be positive for the country, as it would reinforce its commitment to go ahead with the much-needed structural reforms,” Dionisio says. “It could also improve the transparency levels of the country, which I believe would be something that would be greatly valued by investors.”

Structural reform of the Angolan economy has, however, been a long time coming. The country was unable to diversify the economy during the boom years, and now has to do so at the same time trying to get its fiscal house in order.

“A higher oil price is not a necessary precondition for reform,” Pourcelot says. The government could promote private sector growth by pushing through reforms in the non-oil economy, improve institutional capacity and regulatory frameworks, and work to attract more foreign direct investment. “Similarly, reducing the size of the public sector and red tape, improving transparency and breaking up monopolies in key sectors is needed.”

This latter challenge is huge, and will need to be achieved under the long shadow of the last president, whose family remains influential. Lourenço has tried to differentiate himself from his predecessor by promising to target monopolies, but this could bring him into conflict with the dos Santos family, Pourcelot warns.

“It is too early to tell if reform attempts will be stalled or fall-short since the former president’s clout in terms of the economy and politics is vast,” he says. “Breaking up state monopolies held by the dos Santos family or undermining the vast influence the former president and his family enjoy over the economy could be a source of conflict between the incumbent and his predecessor, and means that the new president has limited room to manoeuvre, suggesting business as usual.” {/mprestriction}